Published November 2025 | Read time 15 minutes

Tom Divers is the founder and creator of Vietnam Coracle. In 2005 he moved from his native London to Vietnam, where he has been living, working and travelling ever since. He pays rent in Ho Chi Minh City but is more often on the road, riding his motorbike a quarter of a million kilometres across Vietnam to research guides to the farthest-flung corners of the nation. When he’s not in the saddle, you’ll find him on a beach with a margarita, in a tent on a mountainside or at a streetside noodle house: in other words, at the ‘office’. Read more about Tom: Q&A, About Page, Vietnam Tourism website.

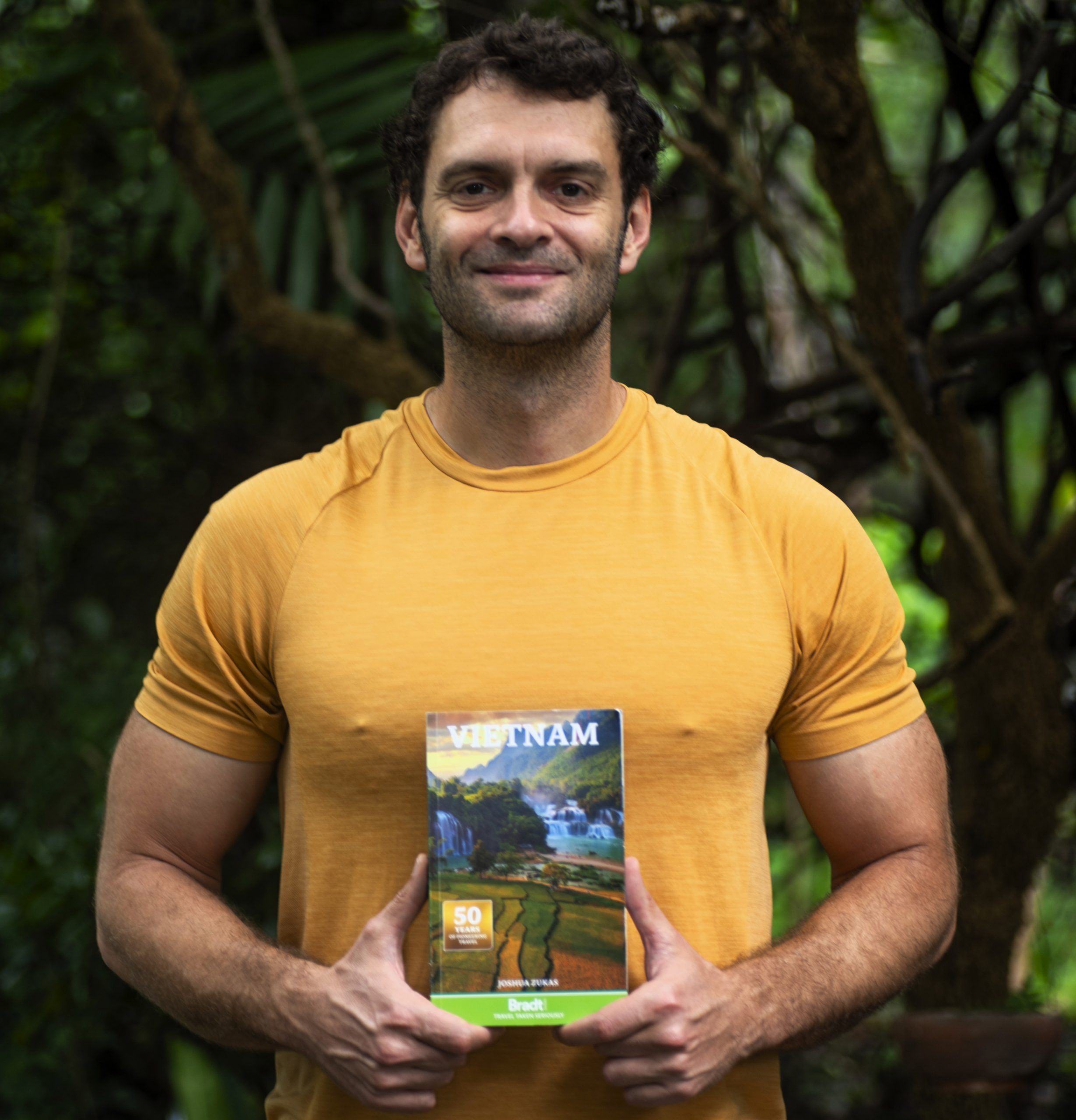

Q&A with a Friend, Contributor to the Site & Author of the Bradt Guide to Vietnam

Joshua Zukas is a travel writer and friend who has written over a dozen articles for Vietnam Coracle, as well as being a regular writer for leading guidebook brands, such as Lonely Planet and Michelin. In August 2025, his new Bradt Guide to Vietnam was published after two years of research. I first met Joshua on the eve of lockdown, in May 2021. It was the beginning of the fourth wave of the pandemic. We were both staying at the same hotel in Cần Thơ in the Mekong Delta. There were no other guests. One morning at breakfast, we started chatting together. It didn’t take long to realize that we’d both admired each other’s work for years, despite never having met. I had read Joshua and his partner Biên’s website, Hanoi Hideaway, and emailed to say how impressed I was. Joshua knew Vietnam Coracle and had even donated to the website. We became friends and, in 2023, Joshua became a contributing writer for Vietnam Coracle. Since then he has written 14 guides, articles and reviews for the site while simultaneously working on the Bradt Guide and numerous other projects for travel publications. In turn, I contributed a chapter to his Bradt Guide. Joshua finished writing for Vietnam Coracle in the summer of 2025. So this is a good chance for me to say thank you for all the good work and support over the last couple of years, and to ask Joshua some questions about his work. Joshua’s full Vietnam Coracle archive is available here and you can buy his Bradt Guide to Vietnam here with a special 25% discount.

[Back Top]

INTERVIEW: JOSHUA ZUKAS

To celebrate the publication of Joshua’s Bradt Guide to Vietnam and his work for Vietnam Coracle, I interviewed him about a range of topics, including the future of guidebooks, sustainable tourism, why he focuses solely on Vietnam, paid travel content vs online travel advice, and much more (see Questions). The previous edition of the Bradt Guide to Vietnam was published in 1998! So there was a lot of work to do for the new 2025 edition. Joshua spent two years travelling Vietnam to research and write the book. I helped out by writing the Southern Islands chapter, focusing on Phú Quốc and Côn Đảo. I can certainly vouch for the time, effort, care and attention that has gone into creating this guidebook and I’d encourage readers to consider buying it here with a 25% discount.

[For more interviews and articles like this, see Related Posts. And if you enjoy Vietnam Coracle, please support it with a donation]

Questions:

➤ 1. Paid Travel Information vs Free Online Content?

➤ 2. Will Guidebooks Survive?

➤ 3. Why Vietnam?

➤ 4. Decline in Adventurous Travel?

➤ 5. Writing Practices, Methods & Hacks?

➤ 6. Your Perfect Year in Vietnam?

➤ 7. Sustainable Tourism?

➤ 8. Romance of Travel?

➤ 9. What’s Next?

If you like Vietnam Coracle, please support it with a donation or become a member of my Patreon community or purchase an Offline Guide & Map. This website relies on reader support to maintain its independence & quality. Thank you, Tom

Question 1:

Why should someone pay $20-$30 for a physical or digital copy of the Bradt Guide to Vietnam to plan their trip when there’s so much free-to-access information available online – from travel blogs to YouTube channels, AI chatbots to Instagram accounts, and numerous other free resources?

“Put simply: independent, curated, in-depth expertise. This guide offers dedicated street food and café sections for every city, region, and province; dozens of retold myths and legends that add texture to Vietnam’s history and culture; specialist contributions from local journalists, historians, academics, and travel writers; and advice on how to escape the crowds and embrace real adventures in all their haphazard, spontaneous, maddening glory. No YouTube channel, Instagram account, guidebook, or website (except perhaps this one!) matches the same level of insight.

Digital editions may be convenient, but I always encourage people to buy the physical book (yes, Bradt does ship to Vietnam). There’s something far more satisfying about reading in a café or under the glow of a bedside lamp than squinting at a screen or scrolling on a laptop. And best of all – no infuriating notifications.

Why not just rely on free websites, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok or AI chatbots? The short answer: the enshittification of the internet – and, in the case of large language models, AI slop. The democratisation of content creation has its merits, but when it comes to travel research, finding high-quality information through search engines has become nearly impossible. There’s still good material out there, but as the volume of content has exploded, its overall quality has sharply declined. Perhaps the internet will eventually correct itself – but it doesn’t seem likely anytime soon.”

Question 2:

Do you think established big-name guidebook brands, such as Lonely Planet, Rough Guides and Bradt, will survive the next 10-20 years in their current format or will they need to adapt and change in order to continue? And if so, how might they do this?

“Like everything else, the guidebook industry must evolve or risk extinction. You may have noticed that it’s already changing. To cut costs, Rough Guides increasingly relies on desk research and no longer requires writers to visit every place they cover. Continue down that road, and their books may become time capsules: beautifully written, at times even lyrical, yet nearly useless for modern trends or restaurant recommendations.

Lonely Planet, to its credit, still insists on on-the-ground reporting. But it, too, has shifted focus – trading context and practical details for more photographs, bite-sized sidebars, and “experiences” that cluster themed attractions together. They also commission more local writers than they used to – at least in the case of Vietnam. This is a welcome move that adds local insight to the most recent edition.

Bradt, on the other hand, has doubled down on depth. Rather than commissioning writers to fill pages, it collaborates with them – allowing authors to pursue their own passions, whether history and art or, in my case, sustainability, architecture, myths, and food. The result is a distinctively personal touch. Reading a Bradt guide feels less like consulting a manual and more like being shown around by a trusted friend.”

Question 3:

You have travelled and spent time in several different countries: why write about Vietnam and not somewhere else? Is there something ‘special’ about Vietnam – something that makes it more appealing to write about, explore and live in than any other country you’ve visited?

“I get this question a lot – and I really should have a better answer by now! I’ll do my best to keep it succinct. First, it’s the stories. I’ve always loved a good tale, and Vietnam is overflowing with them – from centenarian myths and legends to the layered histories of its heritage buildings. The country is a storyteller’s paradise, and it’s such a joy to uncover these tales, research them and repackage them for others to discover. Second, it’s Vietnam’s capacity to surprise. Life here can be inspiring; it can also be maddening. But it’s never, ever dull – and that unpredictability is part of what keeps me hooked.

And finally, perhaps most importantly, it’s the people (cliché I know). I don’t doubt that there are places in the world where people are friendlier, more polite or more hospitable. But Vietnam has this playful energy that I haven’t encountered anywhere else. In the introduction to my Bradt Guide, I wrote about how banter flows freely and this fast-tracks relationships. I wrote those words nearly a year ago, but I believe in them now more than ever.”

Question 4:

In the post-pandemic era, do you think travellers to Vietnam are less adventurous – less likely to go off the beaten path and visit alternative destinations – than they were before Covid? I’m not interested in data, I want to know your opinion based on your experience and observations travelling around Vietnam before and after the pandemic.

“Anecdotally, it does seem that travellers are less adventurous than they once were. Recently, I was on an assignment in Long Xuyên, a sizeable town in the Mekong Delta with much to offer: a floating market, local specialities, pre-war architecture, kaleidoscopic sunrises and sunsets, and that easy-going, hospitable Miền Tây charm. Yet, I seemed to be the only foreigner in town – and certainly the only tourist at the floating market. I remember thinking: this is Vietnam’s biggest year for tourism, and high season (for Westerners, at least) has only just begun – so where is everyone? Of course, I already knew the answer. They’re all crowding the streets of Hội An or taking photos on Hanoi’s Train Street.

Still, I can’t quite bring myself to believe that adventurous travel is gone for good. During the pandemic, people spent long months at home – doomscrolling, watching YouTube, and compiling mental bucket lists (forgive the phrase). Once they’ve ticked off those familiar boxes (again, forgive the phrasing), I think the appetite for real adventure will return. Perhaps it just takes time, after a seismic and destabilising event like a pandemic, for travellers to feel ready to step beyond their comfort zones again.”

Question 5:

How do you write? Do you find it easy or difficult? Do you have any personal protocols, hacks, habits, routines or systems? Do you enjoy the process or is it all a bit of a slog but ultimately worthwhile for the sense of fulfillment and achievement at the end? Is writing a labour or a love?

“How I write – and how I find writing – depends entirely on what I’m working on. If I’m writing a guide or itinerary, my goal is to get everything down as quickly as possible without worrying about awkward phrasing or cliched word choice. The focus is on momentum. Once the draft exists, I circle back to refine and shape it. This approach lets me produce thousands of words in just a few hours, and the editing process is often surprisingly swift.

When I’m working on something with more narrative weight or argument – like a feature – I prefer to take my time. Some days I’ll write only a few hundred words, spending hours on a single paragraph, rearranging sentences, testing rhythms, and fine-tuning phrasing. I’ll also revisit interviews repeatedly, looking for the most revealing, resonant quotes – the ones that make a story sing.

It can be a slog when a topic doesn’t capture my interest or when a story refuses to come together elegantly. But most of the time, I genuinely enjoy the process. However hard it gets, there’s always that satisfying sense of fulfilment when a piece finally clicks into place.”

Question 6:

Imagine you have a 12-month sabbatical (from January to December) supported by a generous expense account. The only condition is that you must spend it in Vietnam and divide the year in quarters, changing your location every 3 months. How and where would you choose to spend it? You can choose specific cities, locations, provinces, even particular accommodations. And include your reasons for each choice.

“I’m going to bend the rules a little, if that’s all right. I’ll still divide the year into quarters, but I won’t be packing up and moving every three months. The key to enjoying Vietnam, after all, is to stay spontaneous.

I’ll start the year in Saigon, relishing its bright days and breezy evenings. When the city’s chaos becomes too much, I’ll escape on weekend trips to my favourite corners of the Mekong Delta – Trà Vinh, Cần Thơ, Long Xuyên, and Châu Đốc.

By early March, when the heat sets in (and I’ve had my fill of the city’s sickly sweet noodle soups), I’ll move north to Huế. The rains should have passed by then, and the spring light makes this garden city pop.

Two months in Huế is probably just right, as by May the city becomes unbearably hot. From there, I’ll see out Vietnam’s long summer in Quy Nhơn. The south-central coast has much to explore: beaches always close by, vestiges of the ancient Cham kingdoms scattered inland and easy access to the cool highland cities of Kon Tum and Buôn Ma Thuột.

Finally, I’ll head to Hanoi around October or November – when autumn begins – and stay until the end of the year. Despite the air quality, Hanoi in the cool months is pure magic: warm sunlight by day, crisp evenings and the occasional cold snap that makes wandering the Old Quarter all the more atmospheric. Plus, the bracing mountain air is never far away.”

Question 7:

You hold an MSc in sustainable tourism and I know you are concerned about the environmental impact of travel. Indeed, your Bradt Guide to Vietnam addresses these concerns throughout. Do you think there is a paradox in being a travel writer – encouraging people to travel and, in the case of your specialist country and target audience, specifically long-haul travel – while also maintaining a deep concern for the environment? I think I’m right in saying that long-haul flights are among the most carbon intensive acts an individual can choose to do. How do you reconcile this? Do you feel, for example, that the wider benefits of travel, combined with sustainable practices while in-country, offset the carbon emissions of a long-haul flight?

“I think about this question daily, if not hourly. The short answers are: yes, there’s a paradox; reconciling it is complex; and yes, I still believe travel is worth doing. Estimates for Vietnam vary, but globally one in ten people work in travel and tourism. Imagine if that all stopped – if one in ten people lost their livelihoods overnight. The social and economic consequences would be devastating. Beyond that, travel brings countless intangible benefits to our globalised community: cultural understanding, human connection, and a richer sense of life itself. Just because these things can’t be measured doesn’t mean they aren’t important.

I often return to the academic definition of sustainability, a term I tend to avoid in my writing because it’s so often misunderstood. Sustainability isn’t just about the environment – it has three pillars: environmental, social, and economic. Acting sustainably doesn’t mean focusing solely on emissions or plastic waste while ignoring human welfare or local livelihoods.

Take Phong Nha, for example. Tourism there has lifted hundreds of families out of poverty by providing stable jobs, while stricter regulations have helped protect the surrounding forests and wildlife. If tourism were to vanish tomorrow, it wouldn’t take long for former hunters and loggers – now porters and guides – to return to the jungle to survive.

Ultimately, my mission, if I can call it that, is to encourage people to travel to Vietnam mindfully: to move through the country with intention, contributing meaningfully to its economic, social and environmental well-being along the way. Conveniently, I also believe that this approach leads to a far richer travel experience. After all, who really wants to fly from one carbon-intensive resort to another without learning a thing about the country they’re in? Plenty of people, I’m sure – but they’re not the ones reading my work anyway.”

Question 8:

Do you think there is still any romance in travel today? Or was there ever any romance in it for you personally? Was the romance of travel ever something that appealed to you and made you want to travel and to write about travel?

“I can’t really remember, but I suspect I did feel a sense of romance in travel when I was a teenager. The idea of packing a backpack and venturing into the unknown probably carried a certain idealised, adventurous charm. But whatever romance I associated with travel was quickly dispelled I expect. Travel — or at least the kind of travel I’ve always done — can be uncomfortable, unpleasant, even maddening at times. Romantic isn’t a word I’d use to describe it.

What makes it worthwhile are the people I meet and the experiences I have along the way. I’m not particularly interested in constructing a romanticised idea of travel when the reality itself is more rewarding. And as for whether there’s still a sense of romance in travel today, I can’t really say. Doesn’t it depend on the individual?”

Question 9:

Now you have written an entire guidebook to Vietnam, not to mention major contributions to other well-known travel publications, what is your next ambition as a writer? A short story collection, a play, a novel, a website, your own travel brand and platform, a podcast, guides to different countries, or something else entirely?

“To be completely honest, I’m not entirely sure yet. Ideas are slowly taking shape as I recover from two years of intensive guidebook research and writing, but nothing’s set in stone. I’ve been toying with several possibilities: launching a travel company for intellectually curious travellers, writing a short story collection that reimagines Vietnamese myths, starting a YouTube channel to share my travel advice in a more accessible format, or going off-piste and pursuing a guidebook for northern Thailand.

For now, though, I’m focused on a series of Vietnam stories and features for various publications that I’m genuinely excited about: one on the return of wildlife in Phong Nha–Kẻ Bàng National Park; another on Long Xuyên and the vanishing art of slow travel; one exploring the impact of digital nomadism on Đà Nẵng; and another delving into Vietnam’s new wave of coffee and cafés. Also in the pipeline are features on Hanoi’s Military History Museum and the overlooked history of Champa. Once those are out of the way, 2026 will hopefully reveal itself a little more clearly.”

[For more interviews and articles like this, see Related Posts. And if you enjoy Vietnam Coracle, please support it with a donation]

*Disclosure: I never receive payment for anything I write: my content is always free and independent. I’ve conducted this interview because I want to: I like Joshua’s work and I want my readers to know about it. For more details, see my Disclosure & Disclaimer statements and my About Page

Always treasured the old Moon travel guides, esp. Thailand by Carl Parkes, a classic. Yes, travelers a lot less adventurous now… or perhaps a better description is when I was younger you went on purpose to where nobody else was, and now it’s the opposite. This is a good thing, at least for us. Old-timey travelers.